Let's delve into the intriguing paradox of Pablo Picasso-a man of complex and often controversial views, yet a creator of significant art. His statement “There are two types of women, goddesses and doormats”, is just one example of his complicated persona. However, instead of delving into a critique of his personality, let's explore a more fascinating angle - his art through the lens of metamodernism. This exploration may help us unravel the mystery of how such a problematic person could produce such profound art.

A Modernist Who (Accidentally) Transcended Modernism?

Picasso is often called an icon of modernism. Moreover, he was the embodiment of modernism's arrogant belief in progress and artistic genius. However, interestingly, his art often transcended what he believed in. Look at "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" (1907). Yes, the painting was revolutionary in a modernist sense, but it already shows something that resembles metamodernist oscillation—a movement between classical painting tradition and its radical breaking.

The Pendulum Principle in Picasso's Work

Metamodernism speaks of a pendulum between different positions. Moreover, Picasso, without realizing it, was almost a metamodernist. His work constantly swung between:

- Classical technique and radical experiment

- Representation of reality and its deconstruction

- Love for tradition and desire to destroy it

- Rational structure and emotional chaos

His "Guernica" (1937) is a perfect example. The painting is simultaneously a political manifesto (modernist aspect) and a universal symbol of pain (metamodernist aspect). It both destroys traditional representation and creates a new visual language.

Reconstruction versus Deconstruction

Here, we come to an interesting point. Although Picasso was famous as a destroyer (remember his famous "Every act of creation is first of all an act of destruction"), his art was paradoxically more reconstructive than deconstructive. He did not destroy the tradition of representation - he recreated it.

His Cubist period is not just the destruction of form. Instead, it attempts to create a new way of representing reality more appropriate to the 20th-century experience. In metamodernist terms, he destroyed not to annihilate but to create something new.

The Play of Intellect and Emotions

Another metamodernist aspect of Picasso's work is the delicate balance between rational construction and emotional expressiveness. His Cubist works, with their cold geometric constructions, are surprisingly full of emotional intensity. Similarly, his 'Blue Period' works, with their appearance of pure emotional outpourings, are actually the result of precisely calculated composition. This balance not only stimulates the intellect but also moves the emotions of the audience.

Hierarchies and Their Destruction

Moreover, here we come to a fundamental paradox. Picasso, being a typical modernist "genius," believed in hierarchies (especially the one where he was at the top). However, his art constantly undermined these hierarchies. His "primitivism," the influence of African masks - were not just stylistic experiments but an (unconscious?) questioning of Western art hierarchies.

Tradition and Innovation: A Complicated Dance

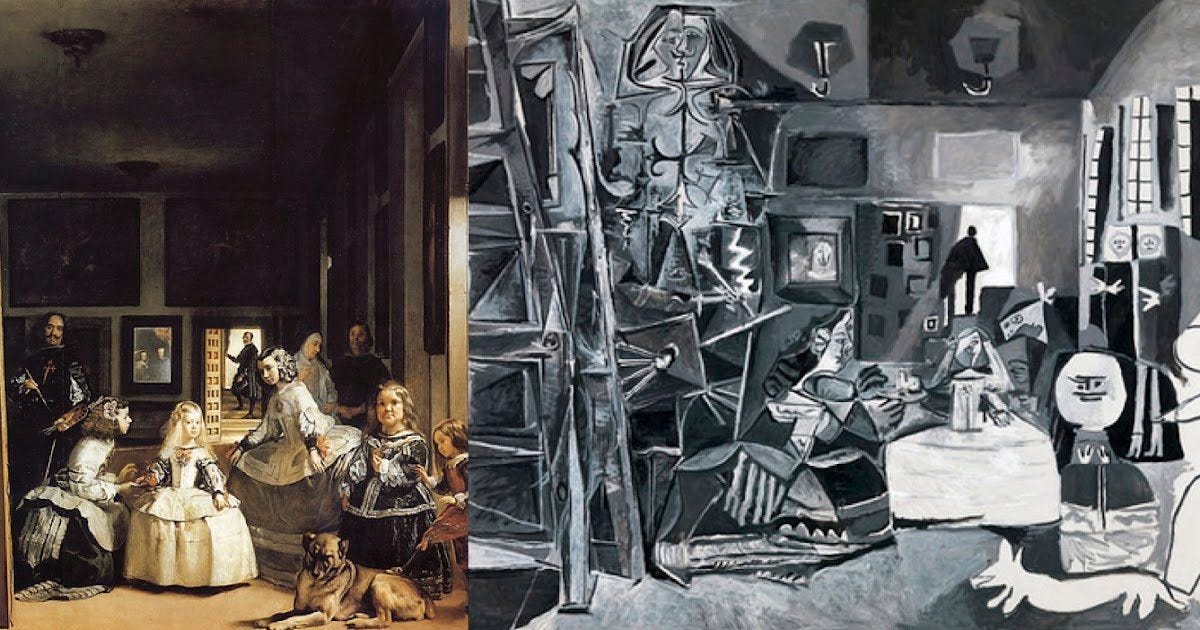

When discussing Picasso's relationship with tradition, one cannot help but smile. A man who said, "Good artists copy, great artists steal" had... let us say, a peculiar view of tradition. However, again - his relationship with art was more complex than his words. He constantly returned to the old masters, interpreted them, "engaged in dialogue" (that is how we politely refer to his appropriation of Velázquez's "Las Meninas"), and did it all with such brazen confidence that it is hard even to be angry.

Sincerity vs. Irony: Who Wins?

Here, we arrive at a fundamental metamodernist question - the relationship between sincerity and irony. Moreover, this is where Picasso becomes truly interesting. His work is surprisingly un-ironic in the context of modernism. Even when he "mocks" tradition (as in his famous bull drawings, where a bull gradually transforms into a few lines), you sense not postmodern cynicism but an almost childlike joy in experimentation.

"The Women Period" (or Why Biography Sometimes Ruins Art)

Ah, and here we come to the most uncomfortable part. Picasso's relationship with women in his life was, to put it mildly, toxic (to put it harshly - terrible). But his portraits of women? They oscillate between idealization and deformation, between love and aggression. From a metamodernist perspective, this could be an interesting example of "oscillation." However, an ethical question arises: Can we separate art from the artist? (Spoiler alert: not always, but sometimes we must try.)

Contemporary View: What Have We Inherited?

Picasso's influence on contemporary art is enormous but paradoxical. He left us:

- The freedom to break the rules (though he mastered them perfectly)

- The courage to experiment (though his experiments were precisely controlled)

- Multiperspectivity (though he was pretty dogmatic himself)

- A revolution in visual language (though he sometimes returned to classical expression)

Was He or Wasn't He a Metamodernist?

As befits metamodernism, the answer is "both yes and no." Picasso was not consciously metamodernist - he was too convinced a modernist for that. However, his art often functioned metamodernistically:

- It oscillated between tradition and innovation

- Combined rationality with emotional intensity

- Created new meanings by dismantling old forms

- Balanced between universality and personal expression

Instead of Conclusions: An Uncomfortable Legacy

Picasso's legacy is complex. He left us:

- Brilliant art (created by a problematic person)

- Revolutionary ideas (expressed in sometimes reactionary forms)

- A new visual language (which was sometimes used to say ancient things)

- Freedom to experiment (though he was pretty dogmatic in his views)

This may be a metamodernist legacy - complex, contradictory, requiring constant rethinking. Picasso was not a metamodernist, but his art helped create the conditions for emerging metamodernism. He was like that old, problematic uncle who, without realizing it, taught us important things - even if those things were "how not to treat women" or "how important it is to separate an artist's talent from their personality."

Alternatively, this whole discussion about whether Picasso was or was not a metamodernist is futile. It is more important to understand that even modernism's most problematic heroes can be helpful for metamodernist discourse - if only we could look at their legacy critically and creatively.

However, one thing is clear—Picasso's art continues to provoke us to ask uncomfortable questions. Perhaps this is the most metamodernist part of his legacy.

Thank you for this article. I am trying to wrap my head around metamodernism in order to use the term in my artist's statement. I have been familiar with its oscillating paradoxical meaning for a few years now. Picasso is one of my most revered artist, though I do not like his treatment of women. It's interesting how you point out his love for tradition in order to mock it in his own innovative way. It's a little experiment that I like to try..You clarification of metamodernism is most appreciated.