How Small Nations Build Grand Hierarchies

A meditation on peripheral trauma and aesthetic colonialism

I’ve been spending half a year in Lahore, Pakistan’s cultural capital, as a guest of a family with multi-generational ties to Cambridge. In their drawing room, art and history intertwine seamlessly: walls adorned with paintings valued not in currency but in provenance, family photographs in silver frames crafted by colonial-era jewelers, and commodes that whisper of British India’s opulent past. Servants bring dinner as the family matriarch shares entertaining memories of trips to Kabul to watch color films. At the same time, her husband, in perfect British English, explains the peculiarities of Mughal architecture.

Yet my mind was elsewhere. That afternoon, halfway through a polo match at The Lahore Polo Club, I’d joined a Zoom lecture for doctoral students at a university from Eastern Europe. This digital bridge to my homeland triggered the cognitive dissonance of the day. Through my laptop screen, I witnessed a peculiar spectacle of post-Soviet modernity: a professor from a tiny Baltic nation confidently advising students to ignore academic journals from Asia and focus exclusively on Western ones (read: Europe and the U.S.). His face showed no trace of doubt, despite the existence of Scopus rankings and simple mathematics – nearly half the world’s population is concentrated in a relatively small area in the East (the so-called Valeriepieris circle). As my visit proves, they might be better read than the average Eastern European.

I recalled how cultural funding experts from my country rejected an application for an artistic project in Azerbaijan – some hadn’t even bothered to Google the actual situation regarding Karabakh. Besides, people from small nations are often assumed to deserve only to travel to Paris. I’d wager that in most minds, there exists a hierarchy of which nations are worthier of historical truth, where wealthier collectors live, or where more educated art consumers reside. Yet I wouldn’t bet on predicting who would be considered a more knowledgeable art expert – a French-speaking Black person who emigrated from Cameroon or an Arab whose parents came from Syria. In small post-Soviet countries, a white woman needs only to want it badly enough, believe fervently, and repeat her self-proclaimed expertise ten times on Instagram reels – and voilà – legitimacy.

The Paradox of Borrowed Colonialism

This paradox – when formerly occupied nations adopt their colonizer’s hierarchical worldview – reflects what Samuel P. Huntington might call a “civilizational fracture” within our own cultural consciousness. In “The Clash of Civilizations,” Huntington argued that post-Cold War conflicts would primarily stem from cultural differences. But here we witness a subtler collision – not between civilizations, but within the fractured consciousness of small post-Soviet nations that, having escaped political colonization, remain trapped between dreams of Baltic grandeur and Western aspiration, fantasizing about cultural domination (or at least winning Eurovision).

On the complex map of global art markets, countries scattered across Europe’s center and eastern periphery simultaneously identify with Western aesthetic traditions while being marginalized within them. Following Edward W. Said’s framework in Culture and Imperialism, we might speak of a peculiar form of colonialism – the adoption of dominant culture’s values and hierarchies, even when they contradict one’s own interests. On the other hand, workarounds emerge – Western market structures are imitated (auctions, galleries, art fairs, biennales) but local rules are created: artists participate directly in art fairs, galleries function as rental spaces for handicraft presentations, auctions sell works without investment criteria. So exhausted by censorship and so convinced of the importance of freedom of expression, quality filters became superfluous.

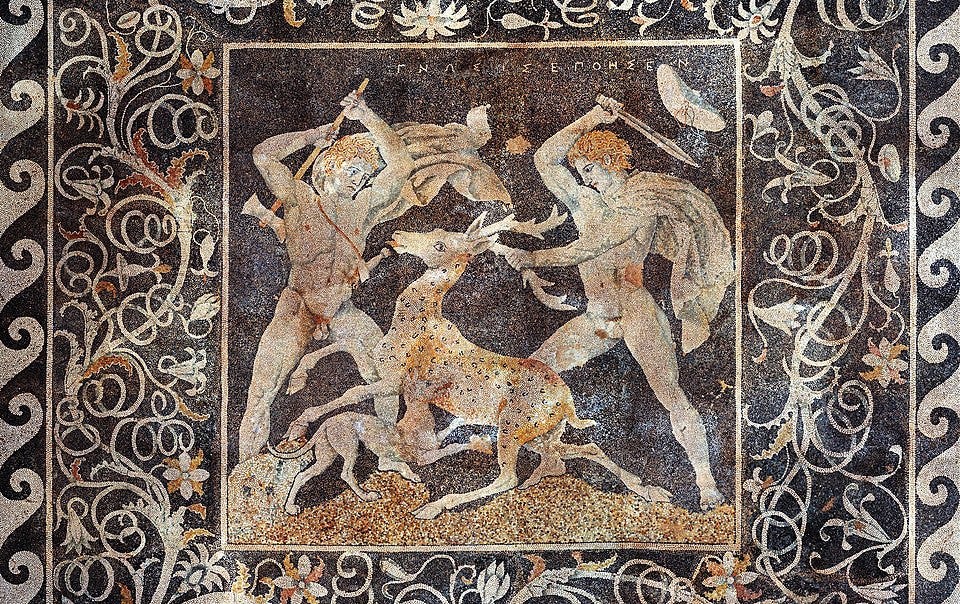

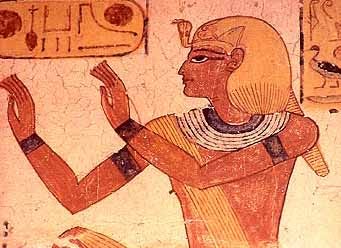

Peter Frankopan’s “The Silk Roads: A New History of the World” reminds us that centers of cultural and economic power have shifted dramatically throughout history. Corridors of influence once ran through Baghdad, Samarkand, and Constantinople before relocating to New York, Paris, and London. Yet, cultural elites in small nations remain fixated on current power configurations as if they were eternal, desperately seeking recognition from Western institutions while abandoning authentic cultural dialogue with countries to the East and South. In our imagination, the East often reduces to Russia or China (images of enemies) or romanticized Japan and India (images of exoticism and spirituality). Meanwhile, vast regions with rich cultural diversity remain largely invisible and therefore often overlooked.

Geographic Hierarchies and the Label of Origin

In the art markets of small countries, an obvious yet rarely acknowledged system of geographic hierarchy prevails. Local collectors and institutions often value artworks not only for their aesthetic or conceptual qualities, but also for their origins. A work created in Berlin automatically gains greater value than an identical piece born in Vilnius, Riga, or Tallinn. A mention of an exhibition in London or New York on an artist’s CV becomes more important than the quality of their work.

This tendency reveals a deeper cultural complex we might call “peripheral trauma” – the feeling that the real cultural center is always “somewhere else.” In art market contexts, this trauma transforms into a value system where origin in cultural capitals becomes a quality guarantee. At the same time, identity from peripheral European regions suggests that work still requires legitimation rituals.

Paradoxically, the same post-Soviet institutions and collectors who demonstrate this provincial attitude toward Western art often adopt the opposite position regarding works from Asia, Africa, or South America. Suddenly, they become representatives of the center, capable of “discovering” and “evaluating” peripheral talents, repeating the same colonial gaze they themselves experience in relations with the Western art world.

The phenomenon Edward W. Said defined as Orientalism – that subtle Western power mechanism that constructs and appropriates “Eastern” identity – takes on a peculiar, almost theatrical form in our region. Nations long on the margins of history, having themselves experienced cultural marginalization from Western Europe, paradoxically become propagators of that same gaze, directing it toward even more distant lands. In this complex psychological dynamic, we see not simple imitation but precisely the continuation of a hierarchical chain – having been diminished, these cultures seek something they themselves can diminish, thus establishing an illusory value in a new, self-created stratification.

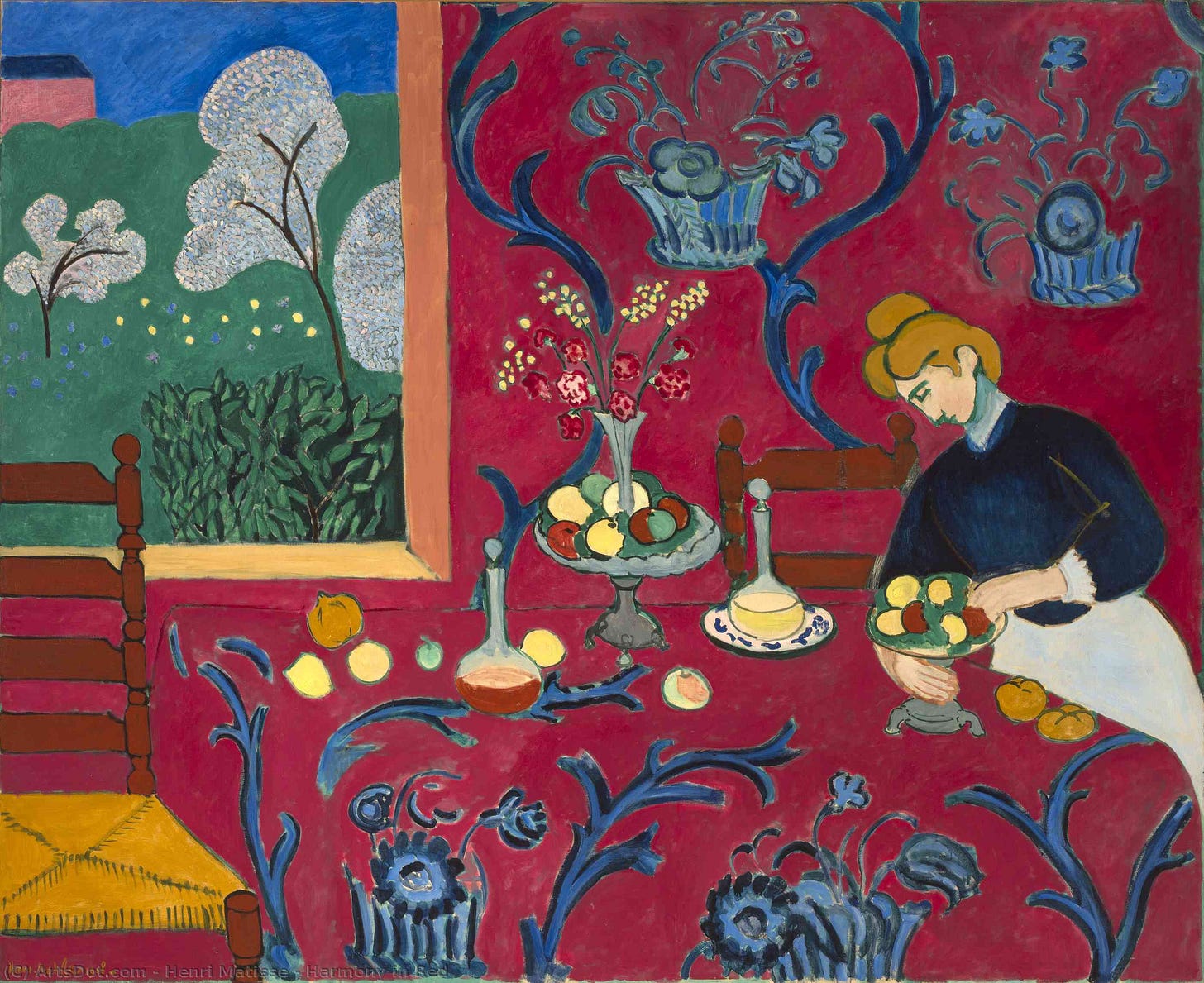

Visual Orientalism: Layers of Modernism and Primitivism

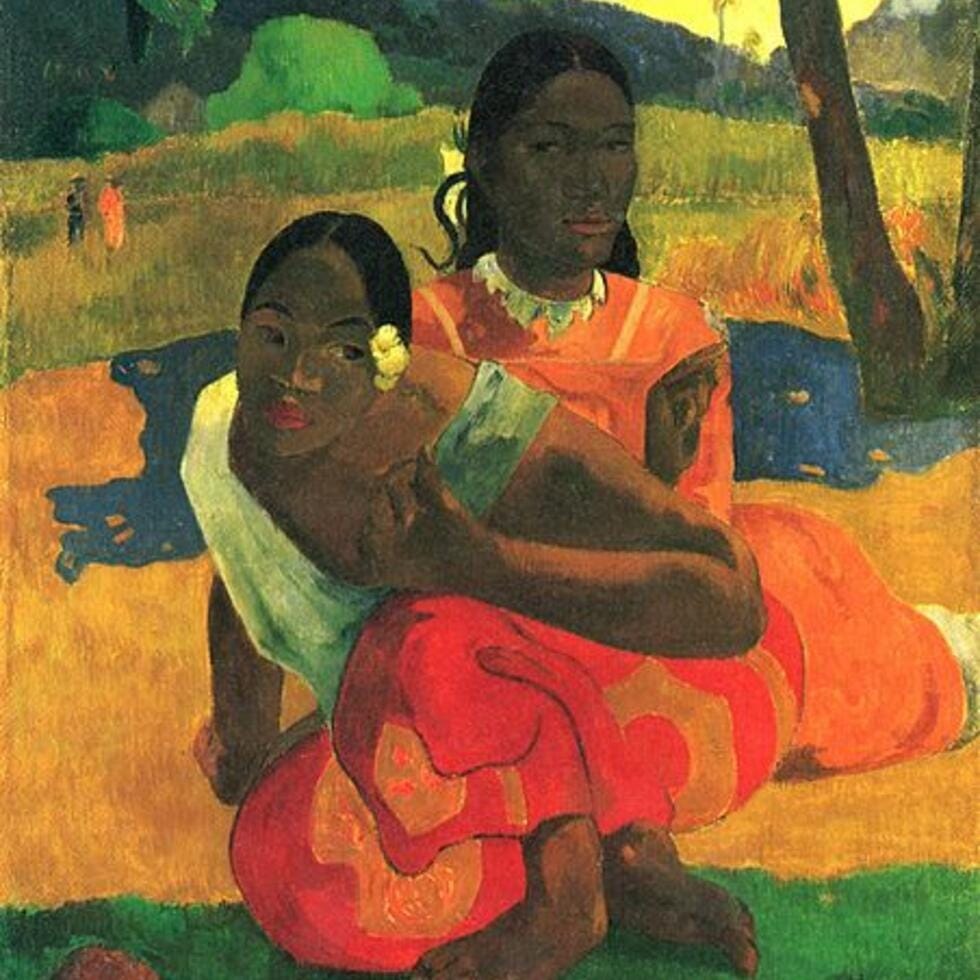

“The West” is not merely a geographic concept but a complex cultural fiction shaped by the colonial epoch and embedded in visual culture. The Modernist movement in Europe was organically intertwined with colonial expansion – fascination with African sculptures or Oceanic masks was not a genuine cultural dialogue, but rather an appropriation rooted in power relations. European artists adopted the formal properties of these visual traditions, severing them from original ritual and symbolic contexts, integrating them into Eurocentric art history as “primitive” and therefore authentically “other.”

In the visual cultures of smaller nations, we see similar processes – relationships with folk art that have long rested on hierarchical principles, where “primitive” forms had to be “refined” to meet professional art standards. Folk art inspirations were valued for their supposed naivety and authenticity, yet they rarely acknowledged folk art itself as a complex system of visual symbolism. Meanwhile, relationships with Asian visual traditions are marked by what we might call “borrowed Orientalism” – we never had colonies in Asia, yet adopted the Western gaze that reduces Eastern art to exoticized stereotypes. Thus, Japanese ukiyo-e prints, or Chinese ink paintings become “subtle,” “spiritual,” or “meditative,” losing their full cultural complexity, assuming all art from these nations is “like that.” At the same time, contemporary creativity seems to be lacking.

Vast cultural regions – Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and the African continent – remain largely uncharted on our cultural maps.

Two Paths Forward: Cultural Trauma and Critical Autonomy

Cultural trauma theory, developed in the works of Ron Eyerman and Bernhard Giesen, offers a productive way to understand our complex relationship with hierarchical systems. Eyerman argues that cultural trauma is not merely psychological but socially constructed, forming collective identity. Post-communist societies bear a specific trauma – the painful peripheral experience that persisted even after regaining political independence.

How can we escape the vicious cycle of oscillating between provincial inferiority and artificial superiority? In visual culture, this dilemma is particularly stark – from an excessive fascination with Western art forms to the superficial exploitation of national symbols.

One path would be recognizing peripheral experience not as a deficiency but as a unique advantage. Artists from small nations who became interesting on the international scene in the late 20th century were often compelling precisely because of their “peripherality.” In their work, they transformed peripheral position into a conceptual advantage, avoiding both provincialism and the label of “exotic Eastern European.” Their post-Soviet experience became a critical instrument for questioning both Western and Eastern visual paradigms.

Another path – actively creating what visual culture theorist Inge Schmidt calls “critical visuality”, the ability to deconstruct power mechanisms of visual representation. This means rejecting hierarchical systems of visual evaluation where the place of origin or institutional recognition takes precedence over the visual work itself. We must shed provenance fetishism, where the curator or collector gaze fixates not on visual language but on institutional legitimation markers.

Angela Onwuachi-Willig’s theory reveals how recognition and acknowledgement of cultural trauma can become the beginning of liberation. In post-Soviet contexts, we can identify double collective trauma – both Soviet occupation and post-communist peripheralization, when culture was automatically positioned as “catching up” to the Western center. Awareness of this trauma is the first step toward creating more authentic visual discourse.

In both cases, the essential step would be to abandon geographic determinism, which automatically links cultural value with specific location coordinates. Instead of constantly positioning ourselves within a global “catching up” narrative, we could cultivate a multidirectional visual consciousness – one that is equally interested in Western, Eastern, and Southern visual traditions, viewing them as potential dialogue partners rather than objects to follow or inferior “others.”

From Aesthetic Colonialism to Networked Imagination

The small post-Soviet art markets’ orientation toward Western hierarchies reveals a deeper problem: aesthetic colonialism that establishes a secondary status in our own cultural consciousness. Liberation requires not only institutional transformation but fundamental shifts in thinking about visuality. The center-periphery paradigm is a historical construct, not culture’s natural state. This insight opens possibilities for creating or consuming visual culture based not on hierarchical but network principles – where different visual traditions interact not vertically but horizontally.

Visual thinking in small nations, instead of imitating supposedly universal Western standards or getting lost in nostalgia, could actively seek new dialogues with other peripheral visual traditions – from the Balkans to Central Asia, from Southeast Asia to South America. In such dialogue, our experiences – Soviet occupation trauma, post-communist transformation, and a long history of resistance to greater powers – become not deficiencies but unique perspectives that enrich global visual discourse.

True visual emancipation begins with the ability to recognize and deconstruct the colonization of one’s own gaze – how we ourselves look at our own and others’ cultures, what evaluation criteria we apply, what hierarchies we (unconsciously) reproduce. This critical awareness opens the path to more authentic visual relationships with the world – one that neither imitates nor rejects but creates independently through dialogue.

Ultimately, genuine visual cosmopolitanism begins not with rejecting one’s cultural context but with critically rethinking it, discovering both its limitations and unique possibilities. Visual culture’s interest lies precisely at those points where different traditions meet, not in a competitive hierarchy, but in a creative tension that enriches both sides.

The original article was written in Lithuanian and published in Nemunas magazine, available online»