Between Art and Kitsch

Imagine this situation: you're standing in front of two paintings. Both depict a stormy sea in the moonlight. Both are technically flawless. Contemporary artists create both. One costs 500 euros, the other 500,000 euros. Why? What distinguishes "serious art" from decorative kitsch? And is this distinction even relevant today?

The Paradox of Kitsch in Contemporary Art

At one exhibition, I witnessed an interesting scene: a group of visitors was having a heated discussion in front of Jeff Koons' sculpture "Rabbit" (1986) reproduction. "This is just an expensive nonsense," one complained. "It's a brilliant commentary on consumer culture!" another countered. "To me, it looks like a luxury store window display," a third chimed in. The discussion nearly turned into a conflict, and at that moment, I realized I was witnessing a perfect illustration of contemporary art's contradiction.

Koons' "Rabbit," whose original was sold in 2019 for $91.1 million, symbolized contemporary art's paradox. It simultaneously exists as a kitsch and its critique, as a luxury object and a commentary on luxury. The gleaming stainless-steel rabbit, based on a cheap inflatable toy, embodies all contemporary art's contradictions.

Most interesting is that Koons never denies the "kitschiness" of his works. On the contrary - he emphasizes it. In his work, we often encounter elements traditionally considered markers of poor taste: glossy surfaces, bright colors, and sentimental motifs. However, the artist uses these elements so masterfully and deliberately that they become part of a complex artistic statement.

Take, for example, his "Celebration" series, where "Rabbit" is one of the critical works. In this series, Koons explores the aesthetics of childhood celebrations—balloons, gifts, toys. These are objects that would typically be considered the quintessence of kitsch. However, transformed into monumental stainless-steel sculptures, they acquire a new dimension. Their surface is so perfect it becomes almost abstract; their scale is so large it creates anxiety; their shine is so intense it becomes almost aggressive.

"Rabbit" becomes even more interesting when we examine its context in art history. The sculpture was created in 1986, at the height of postmodernism, when art actively questioned the distinction between "high" and "low" culture. "Rabbit" can be interpreted as a dialogue with minimalist tradition (perfect, industrial surface), pop art (appropriation of mass culture), and even classical sculpture (traditional pose, monumentality).

However, the paradox lies not only in the work itself but also in its reception. Koons' works are among the most expensive in the contemporary art market, although (or perhaps because) they play with kitsch aesthetics. His "Balloon Dog (Orange)" was sold in 2013 for $58.4 million, becoming the most expensive work sold by a living artist at the time. This raises a fundamental question: does commercial success validate artistic value, or does it question it?

This question becomes even more complex when we see how Koons' works inspire the production of cheap souvenirs. Miniature versions of his sculptures are sold in museum shops - kitsch imitating art that draws from kitsch aesthetics. It's a kind of Möbius strip effect, forcing us to rethink the relationship between kitsch and art and the very concept of value in contemporary art.

Historical Perspective: When Did Kitsch Become Art?

In 1939, art critic Clement Greenberg published an essay defining the relationship between art and kitsch for decades. "Avant-Garde and Kitsch" drew a clear line: avant-garde is good, kitsch is terrible. Greenberg argued that kitsch was a product of industrialization, mass culture imitating "real" art. He described kitsch as "counterfeit sensations," a symptom of cultural degradation.

Greenberg's position was inseparable from its historical context. Fascism was rising in Europe, actively using kitsch aesthetics for propaganda. Modernists, in contrast, sought "pure art" - abstract, intellectual, and detached from mass culture. Jackson Pollock's abstract works perfectly embody Greenberg's theory - no narrative, no sentimentality, just pure painterly action.

However, by the late 1950s, this strict division began to crack. In his "Combines" series, Robert Rauschenberg began merging abstract expressionism with everyday objects - old quilts, stuffed animals, and newspapers. This was the first serious challenge to Greenberg's doctrine.

The 1960s became a turning point. Andy Warhol began mass-producing soup cans and Marilyn Monroe portraits in his Factory studio. Roy Lichtenstein brought comic book aesthetics into galleries, precisely recreating even the effects of printing techniques. Claes Oldenburg created gigantic sculptures of everyday objects. Pop art didn't just break down the barrier between "high" and "low" art - it actively questioned the very meaning of this division.

The Warhol case was fascinating. His "Campbell's Soup Cans" (1962) was revolutionary in subject choice and execution. Warhol deliberately used commercial graphics techniques, silkscreen printing, and mechanical reproduction—everything that, according to Greenberg, were hallmarks of kitsch. Yet this very use of "kitsch" elements became a profound commentary on the nature of art in the age of mass production.

In the 1970s, the Pattern and Decoration movement went even further. Artists like Miriam Schapiro and Joyce Kozloff deliberately embraced what modernism considered taboo—decorativeness. They used "feminine" and "domestic" motifs: flowers, ornaments, and textile patterns. This was also a feminist gesture, challenging the patriarchal assumptions of "serious art."

Postmodernism in the 1980s finally legitimized kitsch aesthetics in art. Julian Schnabel began creating paintings on broken plates. Francesco Clemente combined pop culture images with mythological motifs. Even "serious" artists like Gerhard Richter weren't afraid to experiment with sentimental motifs and decorative elements.

Contemporary Paradoxes

Today, we see an even more complex situation. Let's look at several examples:

Ai Weiwei, one of the most influential contemporary artists, used 1,200 bicycles in his installation "Forever Bicycles" (2014), creating a hypnotic visual effect. Superficially, it could be just a decorative object - like a gigantic kaleidoscope. However, the work speaks about mass production, China's modernization, and the loss of individuality.

Takashi Murakami creates works that, at first glance, look like anime characters or pop culture products. His "DOB" series initially resembles Disney characters. However, behind the kawaii aesthetics lies a deep trauma of Japanese culture after World War II and a complex relationship with Western culture.

Odd Nerdrum creates what many would call kitsch and consciously calls himself the "king of kitsch." His dark, dramatic, often sentimental paintings resemble 19th-century academic paintings. However, this conscious choice becomes a profound artistic gesture.

Marina Abramović's story is fascinating when discussing art value transformations. Her early performances were radical and often dangerous. However, recent projects like "The Artist is Present" (2010) have been criticized for their "spectacle-like" nature.

Does mass popularity automatically mean a decrease in artistic value?

Practical Guide for Art Lovers: How to Distinguish Kitsch from Art?

1. Context Analysis

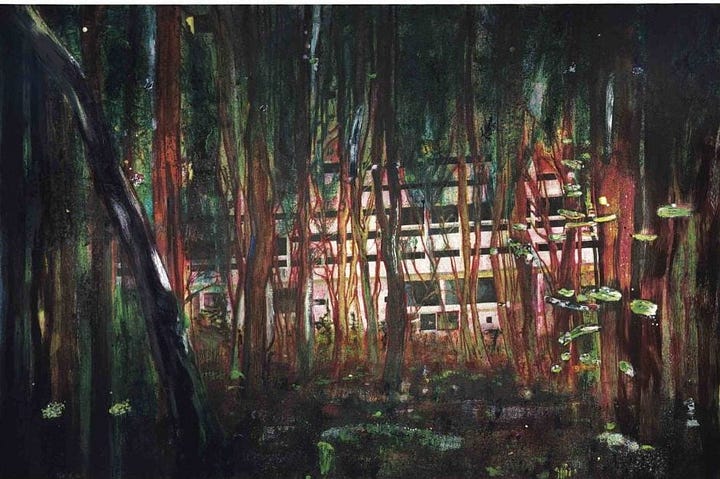

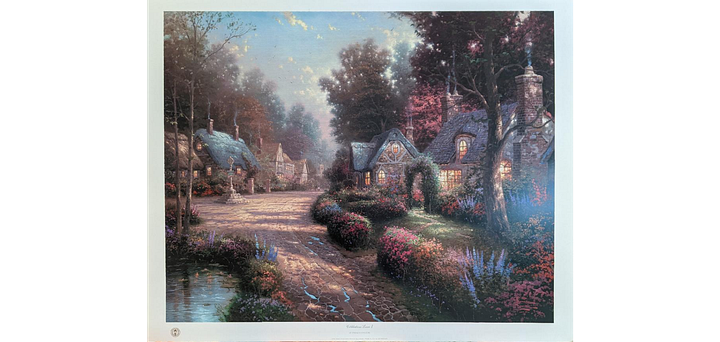

Let's take a concrete example. Compare two landscape painters: Thomas Kinkade and Peter Doig. Both paint romanticized landscapes, often using dramatic lighting and vibrant colours. However, Kinkade is considered a commercial artist, while Doig is one of the most respected contemporary painters.

Why? Key differences:

- Doig's landscapes explore memory, the relationship between photography and painting, colonial history

- His works engage in dialogue with art history and contemporary culture

- Each painting is a unique investigation

- Meanwhile, Kinkade created a formula and repeated it

2. Technical Mastery Assessment

Technical mastery is essential but only sometimes decisive. Jean-Michel Basquiat's works are technically "primitive" but conceptually complex and innovative.

3. Relationship Between Idea and Form

Practical exercise: look at an artwork and ask:

- Does the form serve the idea, or is the idea adapted to the form?

- Does the work engage in dialogue with the viewer, or does it just aim to please?

- Does it raise questions or provide answers?

4. Historical Context

Jeff Koons' "Balloon Dog" would be an entirely different work if created in 1900. Contemporary art is constantly in dialogue with its time.

Practical Recommendations for Collectors

1. Education:

- Visit exhibitions with guides and curators

- Read art criticism and theory

- Follow auction results

- Participate in art fairs

2. Questions to ask before acquiring a work:

- What is the artist's relationship with tradition?

- Does the work add anything new to art discourse?

- How does the work appear in the broader context of the artist's oeuvre?

3. Market perspectives:

- Observe institutional choices

- Analyze critics' reactions

- Follow museum acquisitions

In Conclusion

In contemporary art, the line between "high art" and kitsch has become almost invisible, perhaps even irrelevant. When Jeff Koons' balloon dogs adorn the most prestigious museums and Instagram artists and collaborate with classical galleries, traditional hierarchies no longer suit value analysis.

As philosopher Boris Groys notes in his essay "On the New," contemporary art is "weak"—its value is no longer obvious or universal. It's created through a complex network of relationships between artists, institutions, the market, and viewers. Perhaps this uncertainty is what makes contemporary art so interesting and dynamic.

Today's question of value becomes even more complex due to several factors: technology has democratized art creation and distribution, the global context has changed the rules of the game, artistic practice has become hybrid, and the institutional art world is undergoing transformation.

However, this uncertainty isn't a weakness - it's contemporary art's strength. It allows art to be flexible, respond to a changing world, question established values, and create new meanings. As philosopher Arthur Danto suggests, we live "after the end of art" - not meaning art is no longer made, but it has freed itself from traditional definitions and categories.